The general Balinese philosophy guiding the subak system adheres to the principle of Tri Hita Karana which emphasises that happiness can only be reached if the Creator (God), the people (the farmers) and nature (the rice fields) live in harmony with each other. Based on this philosophy are the ceremonies which are a substantial part of the rice cultivation cycle. The ceremonies are carried out at the various temples which are associated with the subak.

They are organised hierarchically as follow: the simple shrine (chatu) at the individual water inlet, Bedugul temple at the dam or tunnel intersection, Ulun Suwi / Ulun Carik temple at each subak area, penyungsungan subak temple ’sanctuaries which were originally desa temples that one or more subaks helped to worship, after which in the course of time, all the expenses connected with the temple services and offering ceremonials have, gradually fallen to the subak or subaks and Ulun Danu temple, the Baliwide inter-subak temple at the crater lake Batur, the most sacred lake in Bali. For all the temples and other places of worship there are certain times when religious ceremonies are held, either periodically or as occasion demands.

The periodical ceremonies are divided into ngerainin and ngebekin or ngusaba. Ngerainin consists of making a flower offering in the puras ulun charik and penyungsungan subak; it takes place on certain favorable days (rerainan) such as full moon, new moon, Wednesday-Kliwon, Anggara Kasih (Tuesday-Kliwon), and the like, and is performed by the pemangku without the members of the subak being present. No ngerainin takes place at the chatus, which, since they are not puras, do not have pemangkus.

The harvest festival is celebrated in the last stage of the ripening of the rice, in alternate years as ngebekin and ngusaba. New moon is considered a favorable time for ngebekin, while ngusaba takes place at full moon. The former ceremony has the character of an offering to the demons; the latter, primarily a festival of thanksgiving to the deity, is more elaborate than ngebekin and is often accompanied by the Placing of festive Poles of bamboo (penjor) each kesit (field).

The ceremonies are not just performed based on the calendar but also carried out regularly following the stages of rice growth and the sequences of rice farming activities (which are quite similar with the rite of passage) starting from land preparation which is presided by “water opening ceremony”; seeding; transplanting; blooming of rice plant; milking; harvesting until the harvest being stocked at granary. The rituals may be performed individually by each farmer at his own altar as well as in a joint cooperation with other members of the same subak or even different subaks at relevant temples according to the kind of ceremony to be performed.

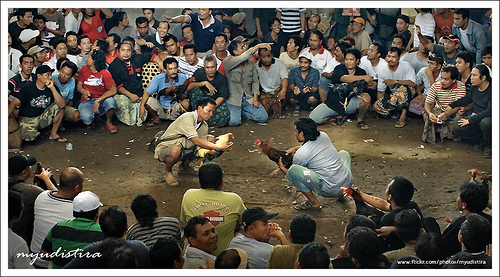

In effort to keep harmonious relationship with other living creatures such as pests and insects, rice farmers in former times used not to kill them, but rather they performed ritual known as nanglukmerana (“avoid pest attack ceremony”). This ritual is still practiced until today by Balinese farmers. The philosophical meaning of this ritual is that not to kill any creature as could as possible but just to protect the crops from pest attack. In some places, many subaks still used to perform “rat cremation ceremony” as a form of nangluk merana ritual, by praying for God’s blessing so that no pest would attack their crops. Other important rituals that need to be mentioned here are the so called tumpek uduh (“flora day ceremony”) and tumpek kandang (“fauna day ceremony”). Each of these rituals is performed every 210 days on Saturday based on Balinese calendar. These rituals symbolizing the biodiversity preservation efforts of Balinese rice farmers.

The Tri Hita Karana philosophy is also the basis for the clearly defined rules of a subak, called awig-awig. This set of laws regulates rights and duties among the members. It includes public obligations, regulations concerning land and water use, legal transactions of land transfers, and collective religious ceremonies. For instance, all members have the right to the same share of water at all times. This principle of equitable water sharing is put into action by fixed proportional flow division structures.

Subak internal matters are handled by the pekaseh, the subak head who is democratically elected by all members of the subak. He is responsible to overlook the irrigation management within the subak area, to schedule cultivation cycles and to organise subak ceremonies. He is supported by several assistants, such as the vice subak head (petajuh), the secretary (penyarikan), the treasurer (petengen or juru raksa), the messenger (kasinoman), special helper (saye) and the heads of the sub-subak groups. Biggersubak are divided into sub-groups, called munduk. Munduk may have a separate inlet from the subakmain canal. A munduk usually comprises an average of 20 to 40 farmers.

Every munduk is headed by a pengliman who receives direct orders from the pekaseh and is responsible for all matters related to the munduk. As a sub-group of the subak, the munduk has to follow the subak rules and regulations. However, certain organisational and water management issues can be decided autonomously on the munduk level. The munduk is an important dimension within the subak. Day-to-day cultivation decisions are made on this level and provide the fine-tuning of the subak water and crop management – not always following the subak laws by doing this. The relationship betweensubak and munduk is to facilitate top down and bottom up information flow.

Members of subak also form an informal group which is called sekaa, in order to make ease a certain working activity on the rice field by working together on a certain field and certain activity. For examples: sekaa numbeg (for land cultivation), sekaa jelinjingan (for water tunnel maintenance), sekaa sambang (for water and pest surveillance), sekaa mamulih (for seed plantation), sekaa majukut (for plants surveillance), sekaa manyi (for harvest work), sekaa bleseng (for carrying paddy to the barn). These sekaa may recruit workers outside subak members. The code of work in these sekaa is simple, “I scratch yours you scratch mine.”

The indigenous social-administration organization in subak also supported by efficient and effective water system. Subak’s water system comprise of many parts such as empelan (dam) functioned as water reservoir, aungan (tunnel), telabah (primary waterway), tembuku aya (primary inlet), telabah gede (secondary waterway), tembuku gede (secondary inlet), telabah pamaron (tertiary waterway), tembuku pamaron (tertiary inlet), telabah penyacah (quaternary waterway), tembuku penyacah (quaternary inlet), tembuku pengalapan (individual inlet), tali kunda (individual waterway). Subak’s water system also has complementary part such as penguras (flushing), pekiuh (overflow), titi (bridge), Jengkuwung (small tunnel), abangan (off-land tunnel), petaku (waterfall structure), and telepus (siphon).

source:blog.baliwww.com/